Life with Father

September 20, 2022

At this time of year, in the lead-up to the High Holidays, I think back to my childhood when I used to sit next to my dear dad in the synagogue. As he stood to say the solemn prayers, I would be right beside him hiding under his prayer shawl (“tallit”) and hugging his leg. That intense feeling of safety and security has never gone away.

This is a tribute to Harry Benjamin Rosenberg, who was my mentor, teacher, and all-around “go-to guy” until he passed from complications from Parkinson’s on May 15th, 2016.

Back in 1998, Tom Brokaw published a bestseller titled The Greatest Generation and it was about the generation of heroes from the 1930s and 1940s who knew about depression, shared sacrifice and war; and then went on to become great leaders. That was the generation that my father belonged to, a rare and dying breed. And my dad was a real hero. He was wise. He was brave. He was a man of his word. Nobody I have met has had a greater moral compass than Dad did. And he led by example.

Dad was born in 1926 in Winnipeg, the youngest of eight children, and raised during the Great Depression. His father died on his 14th birthday, his older brothers had been enlisted to fight in the war, and Dad had to grow up in a big hurry, help run the house at a young age, and frankly never really did experience much of a childhood. I have to say that I didn’t appreciate it enough when I was a kid; what a special learning lesson it was for me to grow up with a Depression-era child as a parent. Not so much the frugality aspect of it, nor even the concept of a penny saved is a penny earned — oh, I can still see Dad scraping the bottom of the peanut butter jar with a spatula just to get that last teaspoon out, or the few drops of boiled water in what seemed to be an empty ketchup bottle — but having instilled in me at a young age that feeling that nothing should ever be taken for granted.

“Waste not, want not” was one of his favorite sayings; something you don’t hear too often today, but it always resonated with me, as old-fashioned as it sounds. Maybe that’s why I became an economist, after all, because the concept of saving for the future was never lost on me, or any of his four children.

I mentioned that Dad had a strong moral compass and one example of this was when I was a child, a developer was going to build a low-rent project adjacent to our neighborhood. Well, a petition went around to stop this from happening and my dad was the only one who didn’t sign it. I remember him telling us, and I couldn’t have been more than six years old, that nobody ever has the right to tell someone else where they are allowed to live. Forty-nine years later, and this is what I remember of my dad — a great example on the basic tenet of how to treat your neighbor.

Dad once told me that things for him could have gone either way. He grew up in a very rough part of Winnipeg, and with no father or older brothers around, he had no role model to speak of. He told me that a turning point in his life, at a young age, was when he decided to say Kaddish for his father after he died, since there was nobody else around to do it, and the men at theshul he went to took him under their wing, taught him Hebrew, taught him to daven and turned a ruffian with no direction into a mensch. He had a job every minute of every day from the time he was twelve, working in the nickel and copper mines of northern Alberta and on the Canadian National Railway as a cook, putting himself through school on his own dime, and ultimately graduating with a Master’s degree in Civil Engineering.

He was totally a self-made man, and while he could have accepted much more lucrative offers in the private sector, he dedicated his professional life to public service and worked his way up the ranks of Environment Canada to lead the government’s inland waters directorate. The Great Lakes project, the St. Lawrence Seaway, and the Fraser Valley diversion all had Dad’s thumbprints on them. In fact, it wouldn’t be an overstatement to say that water was a huge passion of his — even as his Parkinson’s began to eat away at his memory in his later years, if you ever wanted to grab his attention, all you needed to do was say something like “Bruce Heavy Water Plant,” and with his eyes closed he would respond with “oh yeah, that was 1969.” I am sure that we were the only kids on the street who knew the terms “desalination” and “reverse osmosis” by the time we were in the fourth grade.

What is interesting is that Dad’s work life was all about water, and water in Judaism has many symbols ranging from birth, to motherhood, to creation. I sometimes wonder if there was a link between the importance of water in his professional life and the very active shul life he had when he lived in Ottawa — not just that he was the first ever two-time president of Machzikei Hadas in Ottawa, but that he knew the importance of giving back to the community, of being involved, and leading by example countless of times. We are talking about courageous decisions that were made nearly four decades ago to help save the shul financially. And he never once asked for a pat on the back or any recognition because he exemplified humility. As I said, he led by example.

Dad and Mom left Canada for Israel in 1982, opting to spend the rest of their lives with their children and grandchildren, and travel the world; both of them were very curious beings. And Dad still found time to consult part-time and teach math and science to exchange students, again a sign of how important it was for him to share his knowledge, which was vast, and his constant effort to give back to the community.

My mother passed away in March 2011, and what I remember most about her was how she was filled with so much love. And for Dad, what he lacked in outward affection, he made up for in wisdom. He was so wise. And I can tell you, if not for the advice he gave me, I don’t even know if I ever would have embarked on the career path I ultimately chose. It was the fall of 1987, and I was staring at the proverbial fork in the road. I was working for Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation in Ottawa as a Senior Housing Economist earning C$32k per year and I was given an offer at the Bank of Nova Scotia on Bay Street for an intermediate-level job as the Financial Markets Economist for C$28k. I was disappointed with the Scotiabank offer and was prepared to turn it down, but Dad said, “Dave, sometimes you have to take a step back to take two steps forward.”

Words to live by. I still tell that story as often as I can to college graduates who focus solely on the dollar signs instead of their long-term career paths. And that is exactly how Dad responded to his Parkinson’s disease, which he endured for nearly 25 years. One step back, two steps forward. He kept plugging along, adapted to his evolving condition, and he never ever complained. So brave.

I miss Dad terribly, to this day, and especially at this time of year. Rosh Hashana (the Jewish New Year) is also known as Yom HaZikaron — which literally means the Day of Remembrance. If you believe in God, the gift he gave us all that is taken for granted the most is our memory. And my memory of my father is one of a huge success story. Dad made it to 89 years old and defied all the odds considering his illness. He and Mom raised four wonderful kids, had ten grandchildren, as well as eight great-grandchildren and counting. And I know personally that I wouldn’t be the father or man I am today if not for them.

On a final light-hearted note, I want to share this story with you. In 2003, which was my first full year at Merrill Lynch in New York, I was asked to be a keynote speaker at the annual CFA dinner at the Sheraton Centre in downtown Toronto. Ira Gluskin, the iconoclastic investor who hired me six years later, was the other speaker that evening. I recall weeks later being with my dad, and he asked me about the evening. I told him I talked about the economic outlook and Ira talked about his new investment idea at the time, which was income trusts. Dad asked me if I could manage to get him a copy of Ira’s speech, and so I called the people I knew at Gluskin Sheff who sent me a copy of his speech.

The following Sunday I was at my parents’ condo, and I gave Dad a copy of Ira’s speech and I said, “Dad, here’s my speech too, in case you’re interested.” An hour later, I see Dad at the kitchen table devouring some of Mom’s famous cheese blintzes and at the same time poring over Ira’s speech. My speech was still on the counter, untouched. I said, “Dad, are you going to read my speech too, or just Ira’s?” I remember his response as clear as day. Dad quipped: “Which speech is going to help me make money, his or yours?”

Like I said, Dad was very wise.

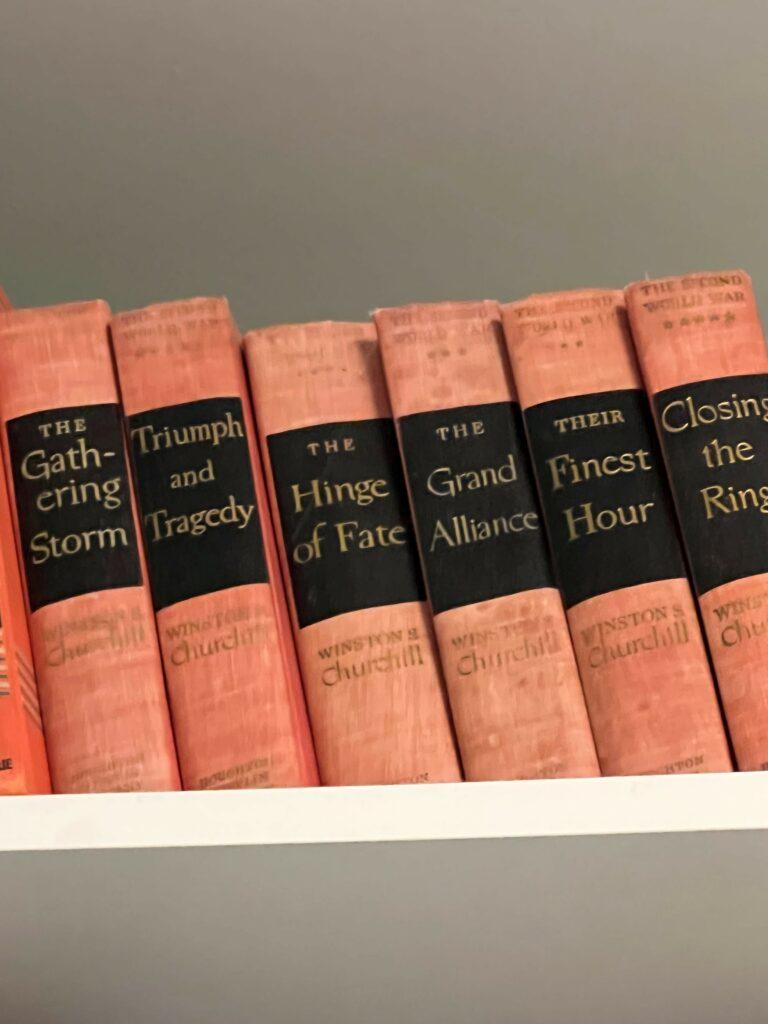

I started this missive off with Tom Brokaw’s masterpiece on The Greatest Generation, and so I will finish off with the same thought. When I say Dad was wise, it was also reflected in the books he chose to read, and he was voracious in that regard. But I never saw him pick up a novel. It was always something on politics, economics, geography, or history. In the house I grew up in, there was a long bookcase in the main hallway near the front door, filled with classics. I noticed that there was this six-book volume of Winston Churchill’s memoirs — the books were so old I think they must have been the first edition. I was a teen at the time and asked Dad if they were his, and he nodded. When I asked if he had read all six volumes, he responded with “twice” (it’s amazing he ever made it onto the golf course!). He then put his arm around me and said, “never, never, never give up.” I am struck by the fact that so many decades later, I can recall that moment with such clear recollection. Then again, this is the time of the year for remembrance.

Recent articles

Rosenberg Research ©2025 All Rights are Reserved